In the shifting tapestry of Edo- and Meiji-era Japan, Jigoku Dayu 地獄太夫—the “Hell Courtesan”—emerged as a figure both mythic and moralizing, embodying the tension between sensual allure and Buddhist impermanence. Draped in robes embroidered with visions of hell, she became an enduring muse for ukiyo-e artists, her beauty forever shadowed by the underworld.

The Legend and Transformation

According to folklore, Jigoku Dayu was the daughter of a samurai who was kidnapped and sold into a brothel. Rising to the rank of tayū—the highest courtesan status—she chose the name “Hell Courtesan” (Jigoku meaning hell, Dayu a title of rank).

Her life took a transformative turn when she met the eccentric Zen monk Ikkyū Sōjun, famed for his irreverent wisdom and unorthodox teachings. Instead of condemning her, Ikkyū revealed to her the Buddhist truths of impermanence and karmic consequence. Moved by his words, she began wearing magnificent kimonos embroidered with hell scenes—Enma-ō, King of Hell, demons, and the suffering souls of the damned. Each garment was a sermon, a reminder that beauty and status fade before the inevitability of death.

Jigoku Dayu in Ukiyo-e

Her striking imagery became a favorite subject for ukiyo-e artists, each interpreting her story through a different lens.

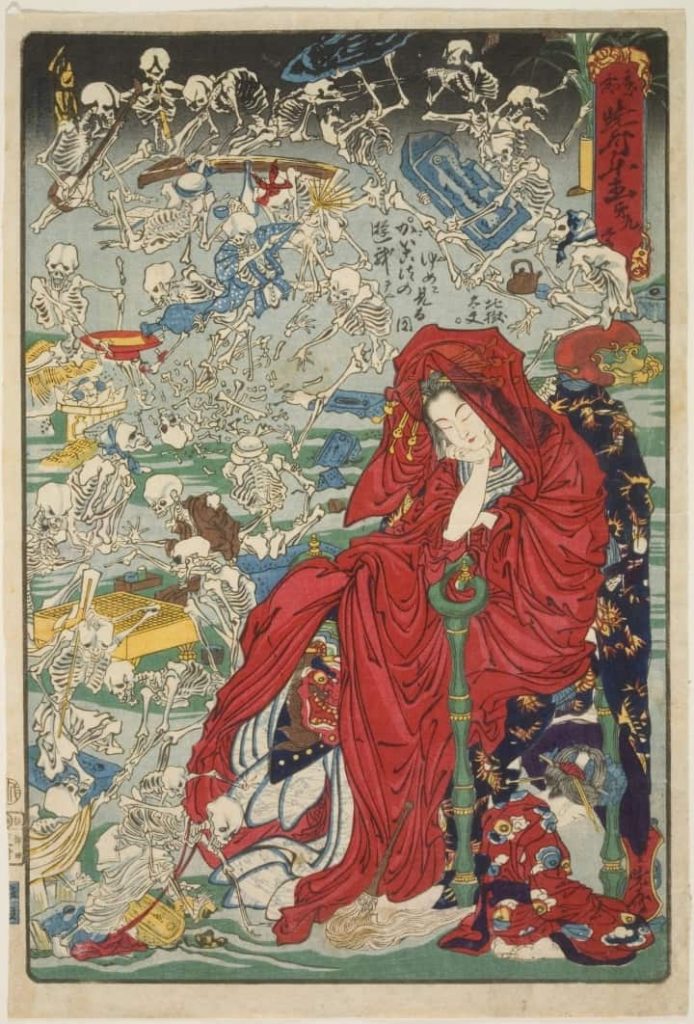

Kawanabe Kyōsai (c. 1874)

In perhaps the most famous depiction, Kyōsai presents Dayu reclining in a vivid red robe as skeletal figures dance around her. The scene is simultaneously playful and macabre—a visual reminder of life’s brevity.

Utagawa Kunisada II (late 1850s)

Kunisada’s portrayal elevates her to near life-size, her kimono a tapestry of hell’s punishments, with Enma-ō presiding. The richness of her garments contrasts sharply with their grim content.

Toyohara Chikanobu (c. 1886)

In a more narrative setting, Dayu walks with two attendants. The hellish imagery on her robe is subtler here, almost hidden—suggesting the coexistence of elegance and darkness.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1890)

Yoshitoshi offers a contemplative image of Dayu in meditation, often accompanied by skulls or skeletal figures. His vision is one of quiet reckoning rather than theatrical spectacle.

Symbolism: Beauty Draped in Mortality

Jigoku Dayu’s story is rich in Buddhist symbolism. Her embroidered robes served as constant visual sermons, reminders of karmic law and the inevitability of suffering. The skeletons that crowd her imagery are not threats but companions—figures of truth, not terror.

In her, artists found the perfect embodiment of the ukiyo (floating world) paradox: indulgence in life’s pleasures, tempered by awareness of their impermanence.

Why Jigoku Dayu Still Captivates Us

Her legend endures because it refuses to be one-dimensional. She is at once an icon of beauty, a spiritual seeker, and a living memento mori. The ukiyo-e tradition—already fascinated with the fleeting nature of life—found in her a subject that could bridge worlds: the sensual and the spiritual, the earthly and the eternal.

For today’s viewer, Jigoku Dayu is more than an artifact of Edo’s pleasure quarters. She’s a reminder that self-awareness can bloom in unlikely places, and that art can carry the weight of both sin and salvation.

Read more:

- Kuniyoshi’s Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

- Hokusai Was Not One Artist, But Many: A Life in Ukiyo-e Transformation

- Why Did Hokusai Move Over 100 Times During His Life?Folktales of Mount Fuji: Myths, Art, and the Spirit of a Sacred Mountain

- The 5 Most Known Ukiyo-e Artists of the Edo Period

- The Art of the Edo Period: A Floating World in Full Color

At the Art of Zen we have a wide selection of original Japanese style art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with some art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments