There are few movements in Japanese art that embody timeless elegance as effortlessly as the Rinpa school. Born in Kyoto during the early 1600s, Rinpa wasn’t a formal academy—it was a lineage of beauty, an unspoken dialogue between artists who shared one belief: that nature could be designed, not merely depicted.

Its name, Rinpa (琳派), fuses Rin from Ogata Kōrin—one of its great masters—with pa, meaning “school.” But unlike other schools, Rinpa had no rigid doctrine. It was a philosophy of refined simplicity, where rhythm and pattern expressed the harmony of nature better than realism ever could.

Kyoto: Where Rinpa Was Born

The Rinpa style first blossomed in Kyoto, Japan’s ancient cultural heart, during the Edo period—a time that also gave rise to the floating world of ukiyo-e (see The Art of the Edo Period: A Floating World in Full Color).

Two figures stand at its origin: Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active early 1600s). Kōetsu was a polymath—a calligrapher, potter, and designer of remarkable sensitivity. Sōtatsu, the painter, was his spiritual twin in visual rhythm and abstraction. Together, they revived the courtly grace of Heian-era art, yet imbued it with modernity.

Their collaborative Poem Scrolls of Kōetsu and Sōtatsu fuse verse, ink, and gold into a meditative harmony. The text flows like water across shimmering paper—proof that art, writing, and design can be one breath.

Designing Nature: The Essence of the Rinpa Aesthetic

If there’s a phrase that defines Rinpa, it’s designing nature—the very theme explored in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s landmark exhibition and catalog Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art.

Rather than depicting nature as it appears, Rinpa distilled its rhythm.

A wave became pure movement. A flower became geometry. A breeze became pattern.

The core traits of Rinpa include:

- Large, simplified forms with bold outlines and repetition.

- Lavish gold or silver grounds that dissolve the sense of place.

- Nature motifs—plum blossoms, waves, irises, grasses—rendered as abstract symbols.

- Harmonious color contrasts and precise spatial balance.

- A refined tension between stillness and motion, fullness and void.

This is where the aesthetic feels so contemporary—Rinpa is both decorative and minimal, ornate yet spacious. It’s design with soul.

The Masters of Rinpa

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active 1600s)

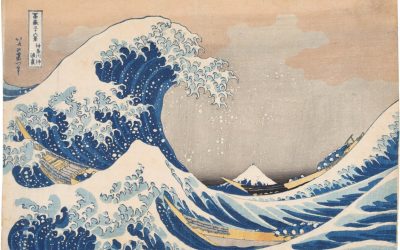

Sōtatsu’s Waves at Matsushima—one of Japan’s most celebrated paintings—turns the sea into pure rhythm. Gold and indigo roll across the surface like sound waves, echoing eternity. His mastery of abstraction influenced generations of artists, from Edo printmakers to modern designers.

Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

A century later, Kōrin reimagined Rinpa’s energy through bold formalism. His Irises screens (Nezu Museum) are a masterclass in repetition, reducing nature to pattern and proportion. Kōrin gave the school its name, but more importantly, he gave it its visual identity: poised, luxurious, yet deeply meditative.

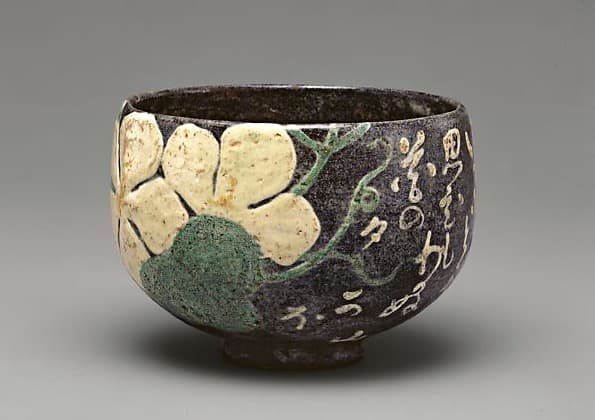

Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743)

Kōrin’s younger brother Kenzan translated the Rinpa sensibility into ceramics. His hand-painted pottery—delicate flowers on earthen glazes—turned functional objects into art, echoing the later mingei (folk craft) ideals.

Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828)

Hōitsu revived Rinpa in Edo with scholarly devotion. In a poetic act of homage, he painted Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons on the reverse side of Kōrin’s Wind and Thunder Gods screens. It was as if two souls were now joined through art.

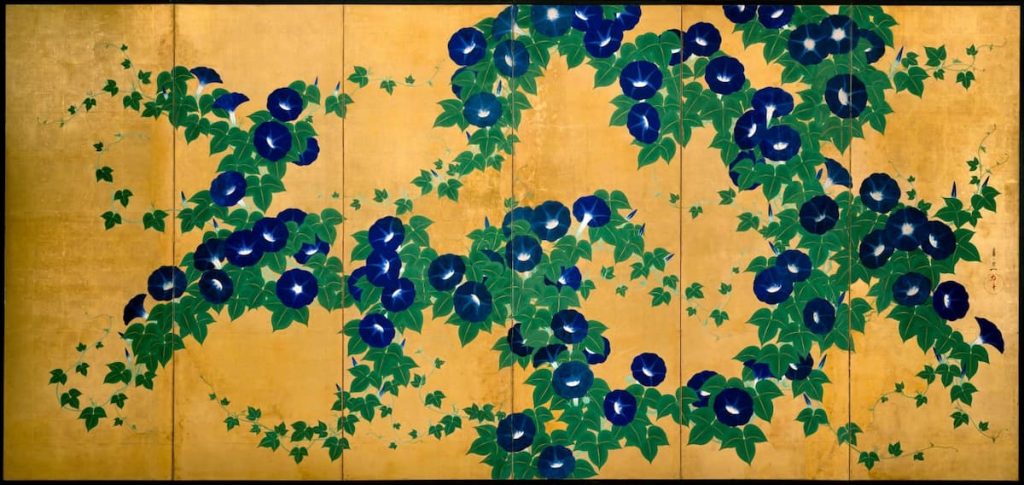

Suzuki Kiitsu (1796–1858)

Hōitsu’s pupil, Kiitsu, carried the torch into the modern age. His Morning Glories shimmer with optimism and precision, showing how Rinpa’s essence—nature distilled into pattern—could keep evolving while staying true to its soul.

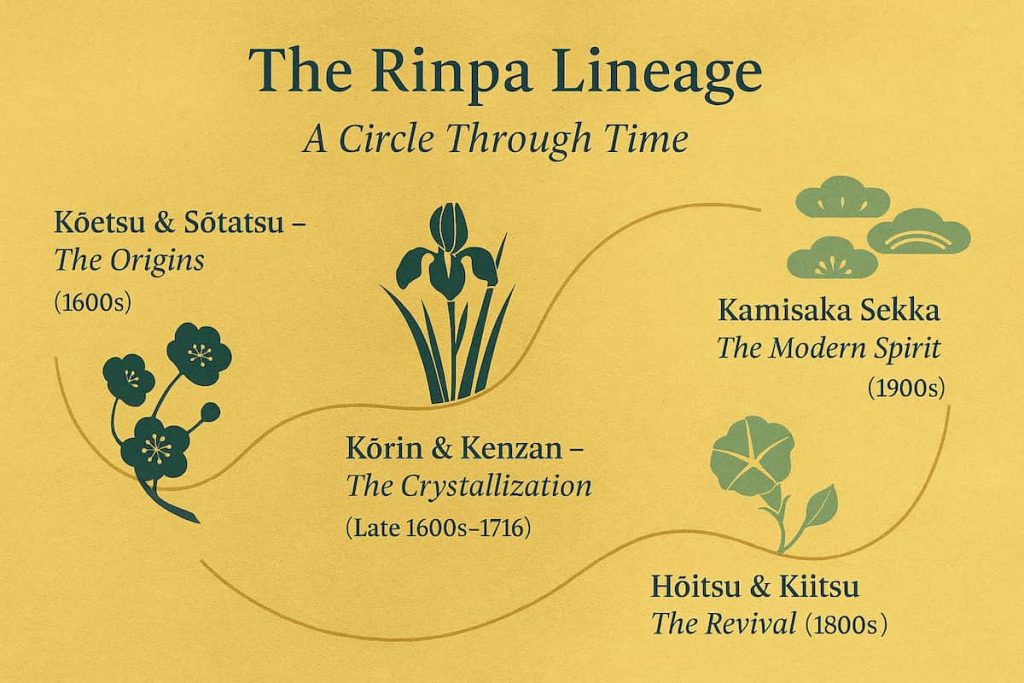

Sidebar: The Lineage of Rinpa — A Circle of Renewal

Rinpa was never a single school, but a rhythm—revisited across generations.

Its name, from Kōrin + pa (“school”), came long after his death, yet it honors a continuum of artists who reimagined beauty as design.

1600s – The Foundation

Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) & Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active early 1600s)

→ Fused calligraphy, poetry, and painting on gold grounds; established the language of rhythm and restraint.

Late 1600s–1716 – The Crystallization

Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) & Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743)

→ Revived and refined Sōtatsu’s vision; distilled nature into geometry and pattern; defined the Rinpa aesthetic.

1800s – The Revival

Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828) & Suzuki Kiitsu (1796–1858)

→ Reawakened Rinpa’s elegance in Edo; preserved it for a modern age.

1900s – The Modern Spirit

Kamisaka Sekka (1866–1942)

→ Carried Rinpa’s rhythm into modern design, pattern, and print, fusing tradition with innovation.

“Rinpa is not a line—it’s a circle of reflection.”

Rinpa’s Influence on Japanese Art

The Rinpa aesthetic became a foundation upon which later Japanese art was built.

Its rhythmic patterns, stylized forms, and poetic restraint directly influenced ukiyo-e, which emerged in the same Edo period. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige inherited Rinpa’s spatial awareness and its gift for turning fleeting moments into timeless design.

This influence continued through the 20th century in the shin-hanga and sōsaku-hanga print movements, which married Rinpa-inspired design with Western realism—something I explore further in The Evolution of Japanese Woodblock Art: Ukiyo-e, Shin-Hanga and Sōsaku-Hanga.

Later, artists like Kamisaka Sekka—the subject of my feature Kamisaka Sekka: A Maestro of Ukiyo-e’s Evolving Canvas—revived Rinpa’s visual rhythm through a modern lens. Sekka’s Momoyogusa (A World of Things) is perhaps the most perfect 20th-century interpretation of Rinpa’s ideals: simplicity, nature, and beauty in design.

The Philosophy Within: Silence, Space, and Flow

Beyond technique, Rinpa carries a deeper philosophy—one that aligns with Zen and wabi-sabi.

The gold leaf that covers so many screens is not mere luxury; it’s emptiness made luminous. The blank spaces are pauses, not absences—what the Japanese call ma (間).

In that stillness, the viewer becomes part of the artwork. Like waves or wind, Rinpa flows between artist and observer. It asks you not to look harder, but to look softer.

The Legacy of Rinpa Today

Even today, the Rinpa aesthetic breathes in modern Japanese design—from kimono patterns and lacquerware to minimalist architecture and digital art. The contemporary collective teamLab carries this lineage forward, transforming nature into living light. Their digital waves and interactive gardens echo Sōtatsu’s golden seas and Kōrin’s rhythmic irises.

Rinpa reminds us that beauty isn’t about detail—it’s about essence. It teaches that art can be bold yet quiet, simple yet infinite.

When I look at Sōtatsu’s Waves at Matsushima or Kōrin’s Irises, I feel the same pulse that animates all great Japanese art: a reverence for nature’s rhythm, a faith in form’s ability to reveal spirit.

Rinpa, in the end, isn’t a style. It’s a meditation.

Read More:

- Kintsugi and the Art of Healing: Finding Zen in What Breaks

- Tansai Gafu: A Forgotten Design Album of Shōwa Japan

- How Kare Sansui Gardens Reflect Japanese Aesthetics and Zen Philosophy

- Furuya Kōrin and Shin Bijutsukai: A New Ocean of Japanese Design

- The Wave Motif in Japanese Art–Its Meaning, Motion, and Memory

At The Art of Zen we carry our own hand-crafted original Japanese art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with brilliant original art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments