From 1615 to 1868, Japan experienced one of the most peaceful and creatively rich periods in its history: the Edo Period. While the outside world spun through revolutions, colonies, and empires, Japan took a different route—closing its borders and turning inward.

But what bloomed within was extraordinary.

Art in the Edo period wasn’t just the domain of emperors or monks—it became something more democratic, more playful, and deeply tied to everyday life. It gave us Rinpa gold screens and Nanga ink landscapes. But perhaps most famously, it gave us ukiyo-e: woodblock prints that captured the pleasures, dreams, and fleeting beauty of urban life.

Let’s dive into how Edo-period art flourished, and how ukiyo-e rose from back-alley entertainment to one of Japan’s greatest cultural exports.

Peace, Prosperity, and the Rise of Merchant Culture

The Tokugawa shogunate, founded in 1603, brought peace after centuries of civil war. With the capital established in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), a rigid social hierarchy emerged—samurai at the top, farmers next, then artisans and merchants.

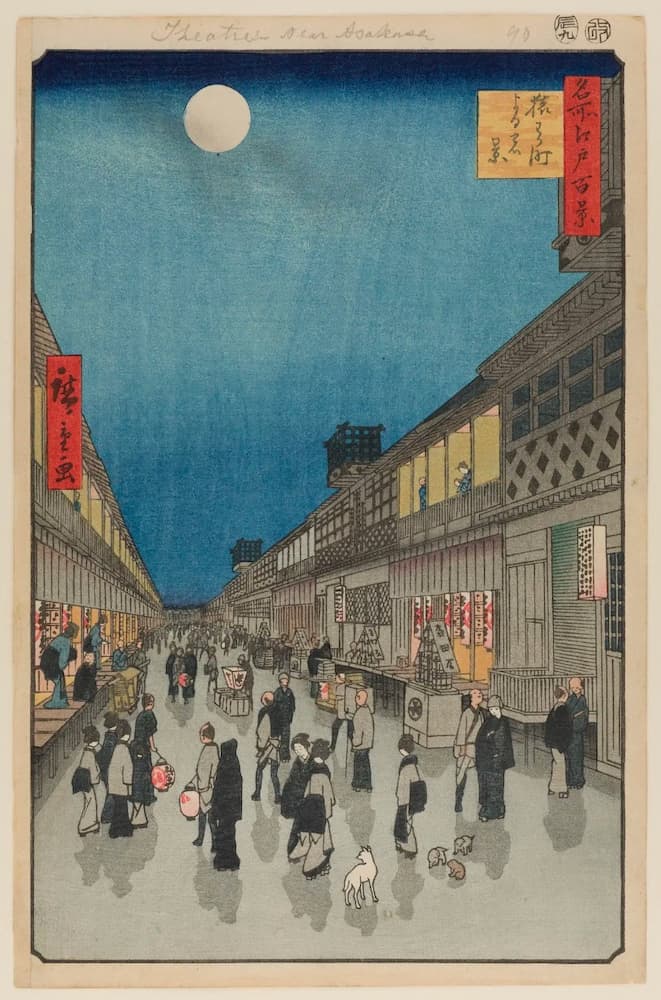

Ironically, those merchants at the bottom became key drivers of a new kind of culture. Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto became bustling cities filled with kabuki theaters, teahouses, brothels, and bookstores. A new kind of pleasure-seeking urbanite was born: chōnin, or townspeople.

They wanted art that reflected their world—not aristocratic court scenes, but actors, courtesans, city streets, snowfalls, fireworks, and lovers. And thanks to the invention of affordable, reproducible woodblock prints, they got exactly that.

Ukiyo-e: The People’s Art

The term ukiyo-e means “pictures of the floating world”—a poetic name for the fleeting pleasures of urban life. These prints were mass-produced using carved woodblocks and water-based inks, allowing publishers to produce hundreds of impressions from a single design.

Unlike traditional painting, which was time-consuming and reserved for the elite, ukiyo-e could be printed, sold, and collected widely. Prices were low enough that even commoners could afford them.

And what were people buying? At first, monochrome prints of famous courtesans or kabuki actors. Later, as color techniques evolved, the subject matter expanded to include landscapes, historical heroes, ghost stories, erotica (shunga), and nature studies.

Additional reading:

- What is Ukiyo-e? A Dive into Japanese Woodblock Prints

- Collecting Ukiyo-e Art: A Guide for Beginners

The Art of Collaboration

It’s important to understand that ukiyo-e was rarely the work of a single artist. Each print was the product of a four-part team:

- The Artist, who designed the image

- The Carver, who transferred it to a series of woodblocks (one for each color)

- The Printer, who applied ink and printed each impression by hand

- The Publisher, who financed, coordinated, and distributed the work

This collaboration gave rise to the rich, layered, and visually sophisticated prints we still admire today.

From Monochrome to Full Color

The earliest known ukiyo-e master, Hishikawa Moronobu (c. 1618–1694), set the tone with strong black-and-white linework of stylish women and bustling scenes. His prints had humor, grace, and a lively energy—setting the foundation for the genre.

Then came color.

In the early 18th century, printers began hand-tinting prints with color. By the 1740s, benizuri-e (pink-printed pictures) appeared. The real revolution came with the nishiki-e technique in the 1760s, developed by Suzuki Harunobu. His elegant prints of courtly lovers and seasonal beauties used up to 10 color blocks—and felt more like paintings than simple prints.

Harunobu’s prints were delicate, dreamy, and poetic. He captured women reading letters in the moonlight, or quietly arranging flowers. In many ways, his work paved the way for later bijin-ga masters like Utamaro, whom we touch on more in our article about the five most famous ukiyo-e artists of the Edo period.

Genres That Defined an Era

As printing technology evolved, ukiyo-e artists explored new subject matter. By the late 18th century, the genre had matured into a colorful mirror of Japanese life.

1. Actor Prints (Yakusha-e)

These dramatic portraits of kabuki stars were immensely popular. Fans collected them like modern celebrity posters. Artists like Katsukawa Shunshō and later Sharaku brought theatrical intensity to these portraits—Sharaku’s work in particular, though mysterious and short-lived, changed the way actors were portrayed, using sharp expressions and bold compositions.

2. Pictures of Beauties (Bijin-ga)

Ukiyo-e didn’t just capture surface beauty—it idealized and sometimes satirized it. Early artists like Torii Kiyonaga emphasized elegance and fashion. Later, Kitagawa Utamaro brought a more intimate, psychological angle, portraying women with individuality and emotional subtlety.

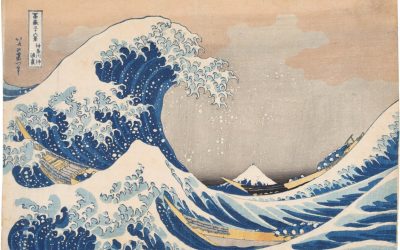

3. Landscape Prints (Fūkei-ga)

In the early 1800s, a shift occurred. Government censorship made actor and courtesan prints riskier, so artists turned to landscapes. What emerged were some of the most iconic images in Japanese art.

Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji and Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō weren’t just pretty vistas. They reflected the soul of Japan: its changing seasons, natural forces, and moments of quiet introspection.

These artists brought new techniques—Western-style perspective, dramatic framing, and imported pigments like Prussian blue—to the genre, giving it international resonance.

4. Warrior Prints (Musha-e) and Myth

Action, fantasy, and heroism exploded in the prints of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, who depicted samurai warriors mid-battle, dragons twisting through the sky, and rebels fighting injustice. His prints captured a hunger for narrative drama and imagination—offering an escape from the orderliness of Tokugawa life.

Additional reading:

- Chūshingura: The Epic of the Forty-Seven Ronin in Ukiyo-e Art

- Samurai in Ukiyo-e and Japanese Art: Guardians of Tradition, Icons of Eternity

- Kuniyoshi’s Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

Beyond the Big Names

While we tend to focus on the household names (Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige), ukiyo-e was a wide field filled with talented hands. Artists like:

- Koryūsai, who bridged elegance and sensuality in his bijin-ga,

- Eishō, a student of Utamaro with a delicate hand,

- Utagawa Kunisada, a kabuki portrait master with commercial success rivaling any of his peers,

- Keisai Eisen, known for both beauties and travel scenes,

…all helped shape the form and broaden its appeal. Many were prolific, with hundreds—sometimes thousands—of designs under their name.

Influence Beyond Japan

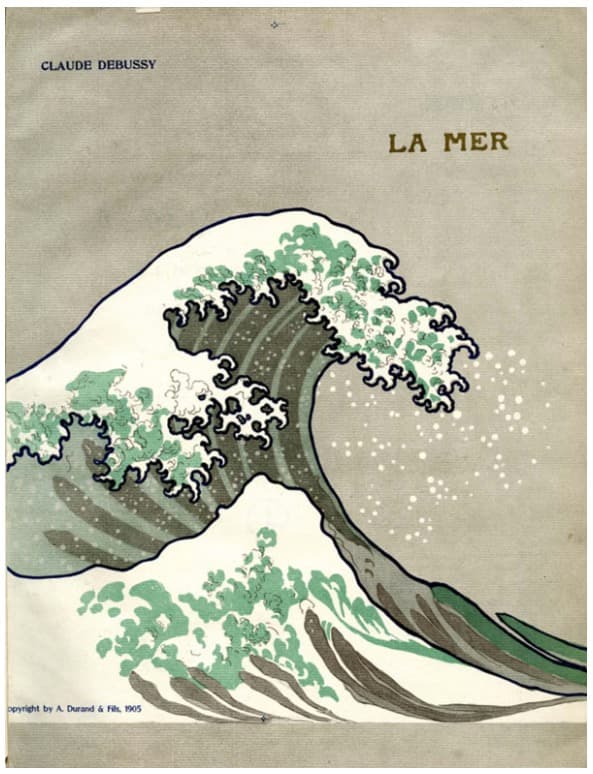

When Japan reopened to the West in the mid-19th century, ukiyo-e prints flooded European markets. Artists like Van Gogh, Monet, Whistler, and Toulouse-Lautrec were immediately captivated by their bold outlines, flat planes of color, and asymmetrical framing.

This sparked a movement called Japonisme in Europe. Ukiyo-e wasn’t just admired—it was studied. It shifted the course of Western art, nudging Impressionists and Post-Impressionists toward new ways of seeing.

A Medium in Decline—But Never Gone

By the 1870s, the Edo period had ended, and with it, ukiyo-e began to wane. Photography, Western-style illustration, and modernization changed public tastes. But the spirit lived on.

In the 20th century, movements like shin-hanga and sōsaku-hanga revived the woodblock print tradition with fresh eyes. And today, contemporary artists and publishers—both in Japan and beyond—still reference the ukiyo-e aesthetic.

In the end, these prints were never meant to last forever. Like the “floating world” they depicted, they were fleeting. But they continue to float—across time, cultures, and disciplines.

Why Edo Art Still Speaks to Us

There’s a simplicity to Edo-period art that feels refreshing even now. In an age where everything is fast, complex, and digital, looking at an ukiyo-e print—a woman pausing in a garden, a traveler caught in a rainstorm, a wave curling above Mount Fuji—slows us down.

It reminds us that beauty can be found in the everyday. That emotion can be captured in a single gesture. And that art, at its best, doesn’t need to shout. It just needs to speak clearly, in the language of color, shape, and line.

Read more:

- 11 Things to Know About Collecting Japanese Woodblock Art

- The Tale of Genji and Its Representation in Ukiyo-e Art

- The Symbolism of Koi in Zen and Japandi Interiors

- The Significance of Japanese Cranes in Ukiyo-e Art

- Why Mono no Aware Is the Soul of Japanese Ukiyo-e

At The Art of Zen we carry a selection of our own hand-crafted original Japanese art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with brilliant original art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments