Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden isn’t just a series of woodblock prints—it’s a bold declaration. From 1827 to about 1830, Kuniyoshi unleashed a torrent of dramatic, tattooed rogues and mythical warriors onto the ukiyo-e world, forever changing how heroism could be depicted.

A Chinese Epic Goes Ukiyo-e

The 108 Heroes are drawn from the Chinese epic Shuihu Zhuan (The Water Margin), a tale of bandits turned righteous outlaws — think Edo’s version of Robin Hood. Their popularity surged in Japan, with novel adaptations and kabuki plays fueling public interest.

Kuniyoshi, son of a textile dyer, captured the zeitgeist at just the right moment. The public wanted rebellion and righteousness, and he delivered it—with swagger, tattoos, and supernatural flair.

108 Heroes: The Title

One of the 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden or “Tsūzoku Suikoden Gōketsu Hyakuhachinin no Hitori” (通俗水滸伝豪傑百八人之一人):

通俗 (Tsūzoku) – Popular, common, mass-market (i.e., for the general public)

水滸伝 (Suikoden) – The Water Margin, a famous Chinese novel also known as Shuihu Zhuan

豪傑 (Gōketsu) – Heroic figure, warrior, gallant person

百八人 (Hyakuhachinin) – 108 people

之一人 (no hitori) – One of them (literally “of these people, one person”)

This phrase is commonly seen in Kuniyoshi’s Suikoden prints, identifying each figure as a single hero among the 108.

Technique & Format

- Medium: Full-color nishiki-e woodblock prints—ink and pigments on washi paper

- Format: Mostly ōban size (~37 × 25 cm), sometimes chūban for smaller sheets

- Publishers: Kaga-ya Kichiyemon (first editions); later Iba-ya Sensaburō

The vibrant color, dramatic shading, and layered composition were unlike anything else in ukiyo-e at that time.

Why This Series Packs a Punch

- Warrior Print Breakthrough

Kuniyoshi’s series was the first large-scale project of single-sheet warrior (musha-e) prints. It cemented his reputation as a master of action-packed design - Tattoo Innovation

Each hero’s body is covered in bold tattoos—dragons, tigers, waves—which defined Edo fashion, later inspiring irezumi and even modern tattoo culture - Narrative Drama

Kuniyoshi’s compositions burst with movement—diagonals, foreground action, dynamic gestures—making each print feel like a live scene frozen in time - Social Resonance

Edo’s merchants and artisans saw themselves in these “outlaw heroes”—men who acted outside authority to uphold justice. The series quietly echoed the tension between duty and rebellion in Tokugawa society

Spotlight on Signature Prints

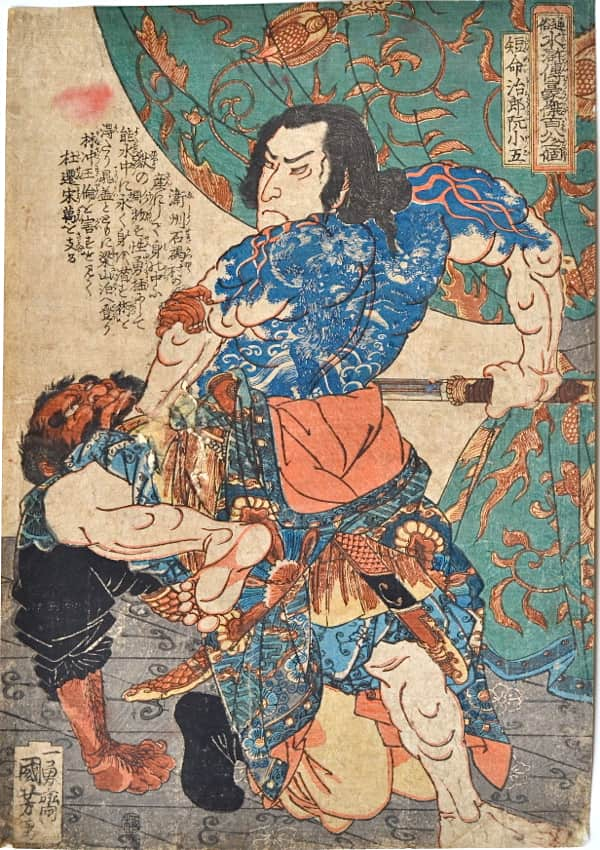

Tammeijirô Genshôgo (Underwater Fighter)

Brooklyn Museum – Tammeijirō Genshōgo, color woodblock on paper, ca. 1823, 36.4 × 25.8 cm

In this print, Kuniyoshi plunges us beneath the waves. Muscular and tattooed, Tammeijirō grapples with an enemy, light filtering through water above. The cool blue bokashi wash merges foreground and background in one fluid scene. Look at that tiger tattoo—an icon of Edo-style ink—winding around his torso. The image is all motion, strength, and silent tension.

Rôrihakuchô Chôjun (Smashing the Water‑Gate)

British Museum – Rorihakucho Chojun (Zhang Shun Smashing the Water‑Gate), oban tate-e, 1827–1830, 37.2 × 25.1 cm

Here, Zhang Shun tears apart a water gate with raw ferocity, a sword clenched between his teeth. Arrows fly and water surges—Kuniyoshi’s signature dynamic diagonals grip the eye. His tattoos almost ripple with movement. The scene screams power, with no room for calm—just heroic intensity carved in wood and ink.

Ryûchitaisai Genshôji (Ruan Xiao’er’s Death Scene)

MFABoston — detailed portrait of a moment of martyrdom

In boiling water, Ryuchitaisai defies capture. Kuniyoshi uses intense diagonal lines, foreshadowing, and perspective to build raw tension—Warrior meets fate in mid-motion.

Kaosho Rochishin (Cutting the Pine Tree)

Chazen Museum of Art (Madison, WI)

This hero fells a pine tree with a single slash—his monk’s rosary hanging around his neck hints at transformation and redemption. Tattooed power meets spiritual undertone.

You can view the entire series of ukiyo-e prints from 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden at the Kuniyoshi Project, one of the foremost online archive of this master’s art.

The Series’ Cultural Aftershocks

Kuniyoshi’s Rise

This series turned Kuniyoshi into one of Edo’s most influential ukiyo-e artists, opening doors to thematic diversity beyond kabuki and beauties.

Tattoo Tradition

The tattoos he printed on paper became tattoo iconography on flesh—fueling Edo’s tattoo subculture and ultimately global styles.

Legacy & Inspiration

Later artists like Yoshitoshi inherited Kuniyoshi’s gusto and emphasis on story-driven, visually narrative prints. Kuniyoshi’s legacy echoes in manga, graphic novels, and pop culture to this day.

108 Heroes: A Ukiyo-e Spectacle

Kuniyoshi’s 108 Heroes series still resonates thanks to its perfect mix of story, spectacle, and emotional intensity. It’s Edo Japan’s version of blockbuster cinema in print—each sheet a heroic, tattooed ode to rebellion and righteous defiance.

If you love the spirit of rebellion and drama in 108 Heroes, and want to see how Kuniyoshi stood among giants like Hokusai, Utamaro, Hiroshige, and Sharaku, check out our article on the 5 most known ukiyo-e artists—each one challenged Edo traditions in their own way.

Read more:

- 11 Things to Know About Collecting Japanese Woodblock Art

- The Tale of Genji and Its Representation in Ukiyo-e Art

- Why Hokusai Manga Was More Than Just Sketches

- The Art of the Edo Period: A Floating World in Full Color

- Kuniyoshi’s Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

At The Art of Zen we carry a selection of our own hand-crafted original Japanese art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with brilliant original art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments