Impermanence is not an idea that most people rush to embrace. We often long for things to last—love, success, beauty, even life itself. Yet in Japan, the recognition of impermanence, or mujō (無常), lies at the very heart of culture. Rather than seeing it as a source of despair, the Japanese tradition has found in impermanence a profound beauty, a poignant sensitivity, and even joy.

This awareness of life’s fleeting nature runs through Zen Buddhism, literature, poetry, design, and the great ukiyo-e prints of Edo. To understand mujō is to glimpse a worldview that transforms change and loss into occasions for deeper appreciation.

The Buddhist Origins of Mujō

The term mujō comes from the Sanskrit anitya, meaning “without permanence.” It passed into Chinese Buddhism as wúcháng before arriving in Japan as mujō. At its core, it describes a simple yet radical truth: all things arise, change, and pass away. Nothing—whether a mountain, a cherry blossom, or a human life—remains unchanged.

In Buddhist philosophy, mujō is one of the Three Marks of Existence (sangai 三解):

- 無常 (mujō) – impermanence

- 苦 (ku) – suffering, unsatisfactoriness

- 無我 (muga) – non-self

Together, these insights reveal why clinging to permanence inevitably leads to suffering. If we can accept impermanence, we begin to loosen attachment and move toward liberation.

For Japan, a land shaped by earthquakes, volcanoes, and typhoons, the teaching of mujō resonated with lived experience. Life was fragile, beauty brief. Buddhist thought simply gave words to what nature was already teaching.

2. Mujō in Classical Japanese Literature

The first great flowering of mujō in Japanese literature comes from the medieval epic Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike, 13th century). Its opening passage has echoed through centuries:

“The sound of the Gion Shōja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sala flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline.”

Here impermanence is not abstract doctrine but lived history. The tale recounts the fall of the Taira clan, once powerful, now gone—like blossoms scattering on the wind.

Poetry, too, became a vehicle for mujō. In the Manyōshū, Japan’s earliest anthology of poems (8th century), poets mourned fleeting loves and praised passing seasons. Later waka and haiku continued this sensibility, distilling impermanence into moments of heightened perception.

Bashō, the master of haiku, captured mujō in seventeen syllables:

Summer grasses—

all that remains of warriors’ dreams.

Time erases even the mightiest ambitions, leaving only grass swaying in the fields.

3. Mujō and Japanese Aesthetics

While impermanence might sound sorrowful, in Japanese aesthetics it becomes a source of beauty. Three interrelated ideas embody this:

Mono no aware (物の哀れ)

Often translated as “the gentle sadness of things,” mono no aware is the sensitivity to fleeting beauty. The most famous example is the cherry blossom. Its blossoms are breathtaking precisely because they fall within days. A Japanese poem might celebrate not just their bloom but also the drifting petals that scatter on water or cling to a kimono sleeve.

Wabi-sabi (侘寂)

Where mono no aware sees impermanence in nature, wabi-sabi finds it in objects. A tea bowl with a crack repaired by gold, an aged wooden beam, a weathered stone lantern—these imperfections embody time’s passage. Rather than discarding them, Japanese tradition honors them. Wabi-sabi is impermanence made tangible, teaching that beauty deepens with age.

Yūgen (幽玄)

The aesthetic of yūgen refers to a mysterious, subtle depth—something suggestive rather than explicit. It is beauty that arises from what cannot last or be fully known. A moon half-veiled by clouds, a flute heard from afar, the hush before autumn dusk—all are examples of impermanence hinting at hidden depths.

These aesthetics are not isolated ideas. Together they express how mujō enriches art and life, turning the fleeting into the profound.

4. Mujō in Ukiyo-e and the Floating World

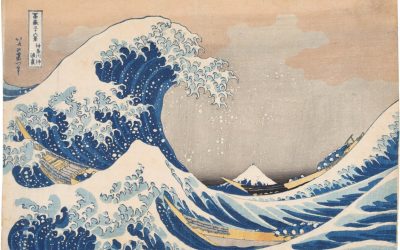

Perhaps no art form captured impermanence more vividly than ukiyo-e.

The word ukiyo originally carried Buddhist overtones of “the sorrowful world,” always shifting and unstable. By the Edo period (1603–1868), the term was reimagined as “the floating world”—a playful, transient realm of courtesans, kabuki actors, and city pleasures. Life was short, so one might as well savor its delights.

Woodblock prints became the perfect medium for this worldview. They froze moments destined to vanish:

- A kabuki actor in a dramatic pose, his performance lasting only a season.

- A courtesan at the height of fashion, soon to be replaced by the next beauty.

- A sudden shower drenching Edo, the rain already moving on.

Hiroshige’s Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge at Atake is a masterwork of mujō. Figures run across the bridge, huddled under straw hats as a burst of summer rain pelts down. The print holds the storm at its peak, though we know it will pass within minutes.

Hokusai, too, infused his landscapes with impermanence. In Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, waves crash, clouds roll, travelers rush along roads—all in motion around the mountain. Even Mount Fuji, seemingly eternal, is shown erupting in his illustrated books.

Through ukiyo-e, impermanence became not just doctrine but spectacle—vivid, colorful, and accessible to the masses.

5. Zen and the Practice of Impermanence

In Zen Buddhism, mujō is not only an idea but a practice. Meditation itself is an exercise in watching impermanence unfold. Thoughts arise, linger, dissolve. Breath enters and leaves. Awareness flickers like a candle flame.

Koans sometimes press the point. A master may ask: “Show me your original face before you were born.” The question turns the student toward the transient nature of self.

Zen arts embody impermanence in material form. In kare sansui (dry landscape gardens), raked gravel patterns shift with each passing hand. In the tea ceremony, each gathering is marked by the phrase ichigo ichie (一期一会) — “one time, one meeting.” The utensils, the flowers, even the conversation—none will repeat.

Seasonal rituals such as hanami (cherry-blossom viewing) and tsukimi (moon-viewing) also carry Zen overtones. They encourage savoring what is here now, knowing it will not remain.

Sidebar: Mujō and Mono no Aware

Mujō (無常) and mono no aware (物の哀れ) are often mentioned together, and for good reason. Both describe a sensitivity to impermanence, but they operate on different levels.

- Mujō is a Buddhist truth: all things are impermanent. It is the universal condition of existence—philosophical, unavoidable, and often confronting.

- Mono no aware is the emotional response to impermanence. It is the bittersweet awareness that beauty lies in transience. When cherry blossoms scatter in the wind, mujō is the fact of their falling, while mono no aware is the ache we feel as we watch them go.

In short, mujō is the doctrine of impermanence, while mono no aware is the human heart’s reaction to it. Together, they form a uniquely Japanese way of seeing the world: recognizing that all things pass, and finding in that passing a poignant, tender beauty.

6. Mujō in Modern Japan

Impermanence remains deeply felt in contemporary Japan. Natural disasters, like the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, served as stark reminders of fragility. Yet the cultural response often echoed traditional mujō—mourning loss while also cherishing renewal.

Festivals such as hanami continue to celebrate impermanence as joy. Crowds gather beneath the blossoms, drinking, laughing, singing. It is not despite the shortness of the season but because of it that the gatherings hold meaning.

In architecture and design, impermanence inspires innovation. Some contemporary architects draw from wabi-sabi, designing buildings meant to weather gracefully. Designers embrace materials that change with time: copper that patinas, wood that darkens, paper that softens.

Japanese literature and cinema also carry mujō forward. The films of Yasujirō Ozu, with their quiet family dramas, emphasize the inevitability of change. The novels of Kawabata Yasunari capture fleeting gestures, glances, and silences that vanish as soon as they appear.

Impermanence is not a theme to be overcome—it is the very rhythm of existence.

7. Why Impermanence Matters

To Western ears, impermanence can sound bleak, even tragic. But in Japanese culture, mujō transforms fragility into meaning. Cherry blossoms matter because they scatter. A tea bowl becomes more beautiful with age. A woodblock print preserves a moment otherwise lost.

Impermanence does not diminish life—it deepens it. To see mujō clearly is to recognize each instant as unrepeatable. Each encounter, each season, each work of art is precious precisely because it will not last.

In Zen, mujō is both a reminder and a gift: a call to live fully, with presence and gratitude.

Read more:

- The Enso Circle in Modern Design: Influences and Inspirations

- Why Jigoku Dayu Remains One of Ukiyo-e’s Most Haunting Figures

- The 5 Most Known Ukiyo-e Artists of the Edo Period

- How to Embrace ‘Ma’ (間) and Bring Japanese Minimalism Into Your Home

- How Hagoita Turned a New Year Game into Art

At the Art of Zen we have a selection of original Japanese art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with brilliant original art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments