At the dawn of the 20th century, Japanese art entered a new chapter — one where tradition and modernity danced together on the printed page. Among the most dazzling examples of this moment is Shin Bijutsukai (新美術海, “New Oceans of Art”), a richly illustrated design magazine edited by the Kyoto-based artist and designer Furuya Kōrin (1875–1910).

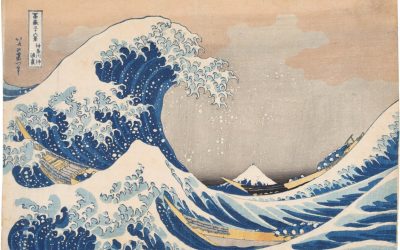

Furuya Kōrin’s work represents more than decoration: it is a bridge between Edo-period aesthetics and the visual currents of the modern age. His prints, brimming with stylized waves, blossoms, grasses, and abstract motifs, spoke to both Japanese craftspeople and a wider, increasingly global audience that was hungry for the sophistication of Japanese design.

Pattern Books Before Kōrin

Long before Shin Bijutsukai, Japan had a rich tradition of publishing design manuals. The first were the hinagata-bon (雛形本), colorless woodblock-printed pattern books first issued in the 17th century. These volumes served as guides for kimono designers, laying out patterns in fine linework that tailors and textile makers could adapt.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, these manuals grew increasingly elaborate, with publishers commissioning some of the most celebrated ukiyo-e artists to contribute designs. Books like Kamisaka Sekka’s Chō senshōgafu and Tansai Gafu by publisher Happō-dō demonstrated that such works could be appreciated not only as tools but as art objects in themselves.

By the time Furuya Kōrin began his career, the line between “design manual” and “art book” had blurred. Shin Bijutsukai epitomized this shift: a design magazine that was itself a collectible artwork.

Shin-Bijutsukai marked the moment when design books were no longer just references, but works of art in their own right.

Who was Furuya Kōrin?

Furuya Kōrin (named in reference to the great Rinpa painter Ogata Kōrin) was part of Kyoto’s vibrant artistic community in the late Meiji era. His illustrations fused traditional motifs — chrysanthemums, plum blossoms, waves, maple leaves — with Art Nouveau rhythms then sweeping through Europe.

Shin Bijutsukai was published in multiple volumes between 1901 and 1902, featuring lushly printed designs in vivid color. Unlike earlier manuals intended only for craftspeople, these volumes were marketed as much to connoisseurs, collectors, and Western audiences captivated by Japonisme.

The timing of Shin Bijutsukai is crucial. In the early 1900s, Japanese art was at the heart of international exhibitions, influencing European design movements from Art Nouveau to the Vienna Secession. Furuya Kōrin’s patterns, with their balance of simplicity and ornament, felt at once ancient and startlingly modern.

The Publisher Behind the Look: Unsōdō (芸艸堂)

Kyoto publisher Unsōdō—founded in 1891 by Yamada Naosaburō—specialized in exquisitely printed art books and pattern albums (zuan‑chō). Their house style fused artisanal woodblock craft with forward‑looking design. Unsōdō’s own history and independent research outline the firm’s origins and enduring commitment to woodblock printing.

From Bijutsukai to Shin Bijutsukai—and Seiei

Unsōdō launched a sequence of design periodicals that defined Kyoto’s pattern culture:

- Bijutsukai 美術海 (1896–1902)

- Shin Bijutsukai 新美術海 (1902–1906) – the “New Ocean of Art,” edited/compiled by Furuya Kōrin

- Seiei 精英 (1902–1907)

A library study from the University of Cincinnati concisely lays out this timeline and confirms that Shin Bijutsukai succeeded Bijutsukai, before Seiei took the baton.

The Museum of Modern Art Library record further notes Shin Bijutsukai as a set of about 36 volumes of color woodcut plates, underscoring its scale and ambition.

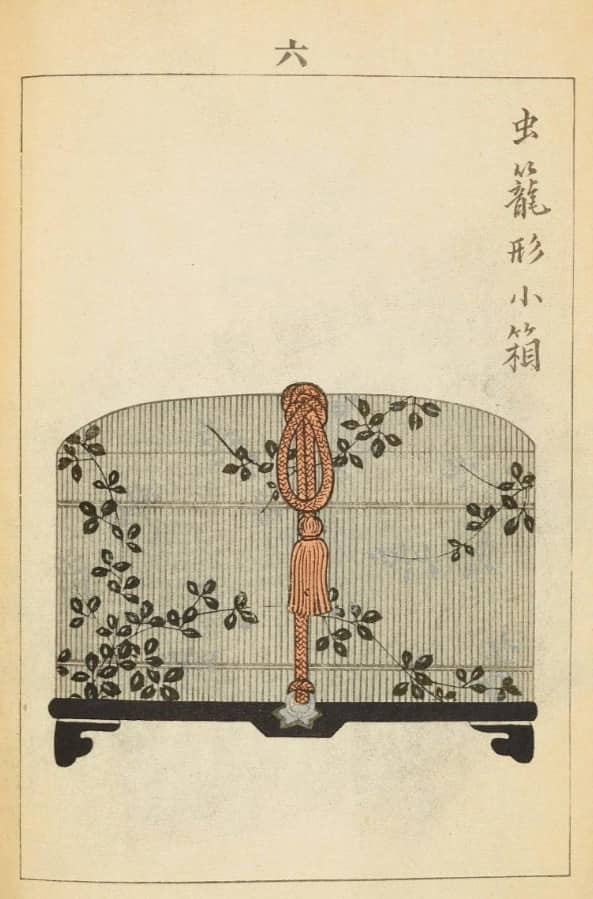

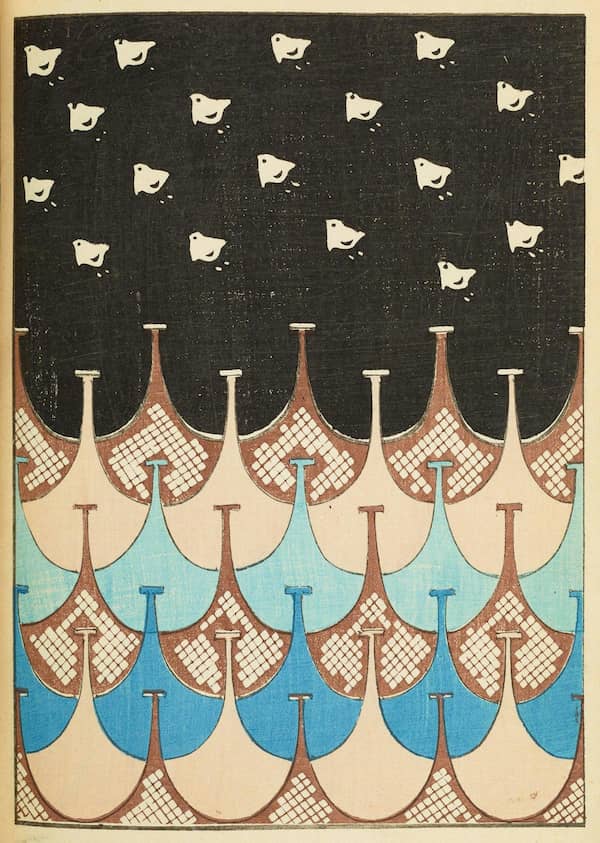

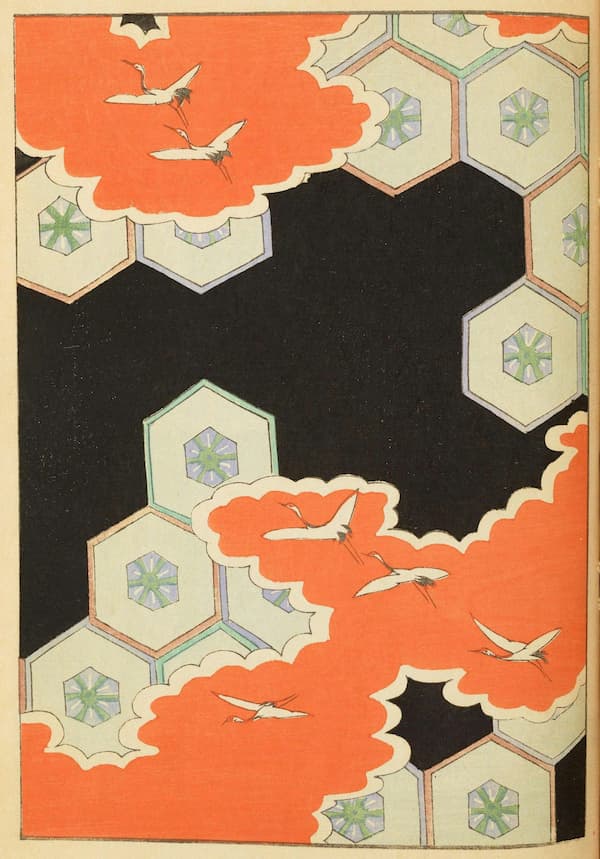

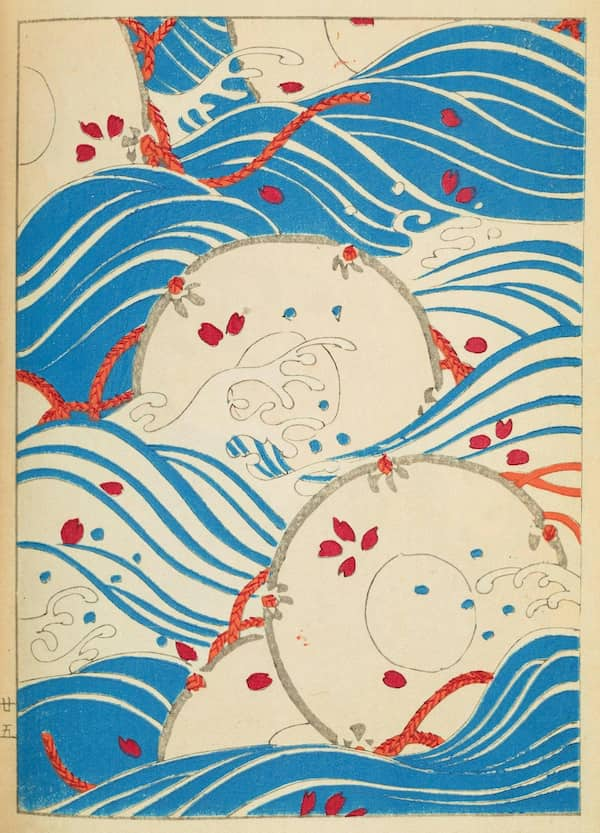

What Shin Bijutsukai Actually Looked Like

Each fascicle presents full‑page, color woodblock plates intended as cross‑craft design prompts—for kimono and stencil makers, lacquer and ceramic artists, book designers, and more. Digitized issues at the Smithsonian Libraries / Internet Archive confirm Unsōdō as publisher and show volumes issued from 1902, with richly printed plates that reproduce beautifully even today.

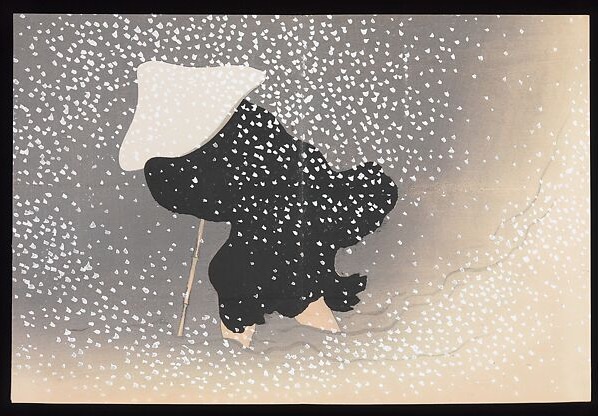

Public Domain Review’s curatorial essay frames the series within the cultural traffic of the era: Japanese artists were absorbing Art Nouveau abroad and repackaging that dialogue for domestic industries—“forging originality through cross‑cultural pollination.” You can see it in the sinuous lines, flattened florals, and dynamic asymmetries across the plates.

Want to browse immediately? Try the Internet Archive scans and PDR’s curated selections; both reveal the magazine’s saturated colors and crisp blockwork.

Anatomy of a plate: motifs, rhythm, and craft

Across Shin Bijutsukai you’ll find:

- Seasonal flora and grasses reduced to emblematic silhouettes.

- Waves, clouds, and mist abstracted into repeatable rhythms.

- Fans, lattice, and geometric interlocks that feel both ancient and startlingly modern.

- Layered fields of color and sharp key‑blocks that preserve line clarity.

These aren’t mere pictures; they’re modular design ideas meant to be adapted across materials. The Smithsonian scans make that pedagogical purpose clear in plate after plate.

Some later or commercial printings note silver or gold heightening on select plates—dealer archives occasionally mention metallic touches—which would track with deluxe woodblock practices of the period, though techniques vary by impression.

How it shaped Meiji design—and why it still reads Zen”

Design historians place Shin Bijutsukai within late‑Meiji visual modernity: it taught artists and industries to look through nature, not just at it. The result is a graphic language of calm repetition, empty passages, and sudden accents—qualities that resonate with Zen and with how many of us design quiet interiors today. Public Domain Review’s analysis highlights that productive dialog with Art Nouveau and Japonisme, which the series retranslated back into Japanese craft.

Though Furuya Kōrin died young in 1910, his legacy endures. Shin Bijutsukai remains a treasured reference for historians, designers, and anyone drawn to the timeless rhythm of Japanese patterns.

For admirers of Japandi interiors today, the lesson is clear. The muted tones, natural motifs, and balance that make Japandi so appealing were already deeply embedded in Japanese design traditions. To look at Shin Bijutsukai is to glimpse the roots of a style that continues to shape how we create harmonious, artful living spaces.

Related books by Kōrin: Kōrin‑moyō (Kōrin‑style Patterns)

To see Kōrin’s hand in a different format, browse Kōrin‑moyō (1907), a two‑volume sample book for Kyoto textile makers. The Met’s entry emphasizes how these albums functioned as pattern libraries for industry while remaining objects of taste. They offer a perfect counterpoint to the magazine’s monthly cadence.

The Met’s Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art provides scholarly context for Kōrin’s pattern books and the late‑Meiji Rinpa revival more broadly.

Kōrin and Sekka: a Kyoto conversation

Kōrin’s circle overlapped with Kamisaka Sekka, the era’s leading Rinpa revivalist and a crucial influence on Meiji design pedagogy. Many catalogues and essays situate Kōrin “with Sekka,” both carrying Rinpa forward for modern life through pattern. For a deeper dive on Sekka’s role and style, see our piece Kamisaka Sekka: A Maestro of Ukiyo‑e’s Evolving Canvas.

Scholarly and museum sources repeatedly link Kōrin’s Kōrin‑moyō pattern albums to this Rinpa‑modern continuum, and they credit Unsōdō with catalyzing that design culture.

Using Shin Bijutsukai in your creative workflow

- Mood‑board a palette: Pick one plate and extract 3–5 hues as a serene scheme for textiles or a Japandi‑leaning room. The clear separations of color make sampling easy.

- Think in modules: Treat each motif as a repeatable element. Build a modern wallpaper, a textile repeat, or a social graphic by tiling, mirroring, or rotating the unit.

- Let emptiness lead: Many plates hinge on generous negative space—use it. Calm fields make accents sing.

- Bridge old and new: Pair a 1902 leaf rhythm with a minimalist sans‑serif poster layout. It’s how Sekka and Kōrin intended these designs to live—across media and time.

Where to view Shin Bijutsukai today

- Smithsonian Libraries Digital Collections / Internet Archive – multiple volumes scanned in high resolution; excellent for research and teaching

- MoMA Library record – series‑level description noting ~36 volumes of color woodcuts.

- Public Domain Review – curated gallery and essay with context on cross‑cultural design currents; images link back to the underlying archives.

A few research clarifications

- The title appears both as Shin Bijutsukai and Shin‑Bijutsukai in English cataloguing; the Japanese is 新美術海.

- Unsōdō’s earlier magazine Bijutsukai (1896–1902) preceded Shin Bijutsukai (1902–1906); the latter is the Kōrin‑edited “New” series. UC’s library post summarizes this progression and also mentions the follow‑on title Seiei (1902–1907).

- Contemporary library records and dealers sometimes cite different start years due to bound compilations and reprints. The Smithsonian/IA and UC sources firmly support 1902–1906 as the active span for Shin Bijutsukai.

References

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art (catalogue)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – Kōrin-moyō (Kōrin-style Patterns), Furuya Kōrin (1907)

- Smithsonian Libraries / Internet Archive – Shin Bijutsukai digital volumes (Unsōdō, 1902–1906)

- https://archive.org/details/ShinBijutsukaiVol1

- (browse additional volumes via Internet Archive search: https://archive.org/search.php?query=shin%20bijutsukai)

- Public Domain Review – “Shin-Bijutsukai: The New Wave of Japanese Design” (contextual essay + curated plates)

- Museum of Modern Art Library – Catalogue record for Shin Bijutsukai (ca. 36 volumes of color woodcuts)

- British Library – “Design books by Unsōdō” (zuan-chō, pattern albums, Kōrin and contemporaries)

- British Library – “Unsōdō, Kyoto’s master of design publishing”

- University of Cincinnati – Library study notes on Bijutsukai, Shin Bijutsukai, and Seiei

While I make every attempt to research the artworks, artists, and publishers throughly, there may be cases where the right conclusions have not been drawn regarding dates, attributions or other items. I welcome feedback on corrections, especially when supporting evidence is located.

Read more:

- 11 Things to Know About Collecting Japanese Woodblock Art

- How Mujō 無常 Inspires Zen Practice, Ukiyo-e Prints, and Modern Design

- Why Mu 無 is the Most Important Word in Zen and Japanese Art

- How Kare Sansui Gardens Reflect Japanese Aesthetics and Zen Philosophy

- How Hagoita Turned a New Year Game into Art

At The Art of Zen we carry a selection of our own hand-crafted original Japanese art prints in the ukiyo-e and Japandi style. Some of our best selling work is Mount Fuji wall art and Japandi wall art.

Add some zen to your space with brilliant original art from the Art of Zen shop.

0 Comments